Queer Resilience:

Activism

01

Lesbian Blood Drives

The AIDS pandemic tested the strength of the queer community, encouraging members to create and strengthen networks of solidarity that would sustain them. During the AIDS crisis, LGBTQ Americans were intentionally prevented from donating blood, a resource that would have directly benefited their community during a moment of health emergency. Instead of accepting this injustice, lesbians

rallied their community members to donate blood directly to sick gay men, filling this institutional gap. Though the exact blood drive pictured here is unspecified (unknown date), those photographed are engaging in a tradition of lesbian solidarity in the Blood Sisters Project. The Blood Sisters, based in San Diego, offered an opportunity to engage directly with the queer community and build networks of support and solidarity with gay men afflicted with AIDS. Many lesbians became involved with ACT UP! and similar organizations because of a sense of community duty (Gould qtd. in Hutchison 120). A sense of “shared responsibility and empathy” guided lesbian organizing during this time and is especially present in the nature of the blood drives (Hutchison 121). Significantly, the blood drive asked lesbians to overcome historical tensions between queer women and men in the name of radical solidarity (Hutchison 121). By donating blood, lesbians were able to contribute material resources and support to their male community members through this crisis. In addition to their roles as emotional support figures and nurses, lesbians stepped up to provide holistic care for gay men, exemplifying the resilience of the group. Though government and public health institutions showed little regard for queer people during this time, the creative support networks developed between lesbians and gay men highlight the importance of interconnection and generative dependence for the LGBTQ community.

Women giving blood at a Lesbian Blood Drive. Lambda Archives.

02

Katrina Haslip

This image (1990) centers Katrina Haslip, a women’s health activist involved with ACT UP!’s organizing. Her distinct position as a formerly incarcerated Black woman gave her unique insights into the intersectional realities of the 1980s AIDS crisis. Through the beginning years of the pandemic, the myth that women could not contract HIV-AIDS was persistent. With white gay men as the poster children of the crisis, women, especially women of color, were left behind in organizing

(Adler). In the public health and medical space, women were systematically excluded from the few resources available for HIV-positive people during this time. A narrow case definition for HIV left out important symptoms that could only present in people with uteruses, including cervical cancer, chronic yeast infections, and more (Adler). As clinical trials emerged as one of few hopes for those with AIDS, women were also systematically excluded because of the possibility that they could become pregnant (Adler). Though the most visible faces of the movement remained white, gay men, HIV-positive women worked tirelessly to fight for inclusive health equity. Their organizing within ACT UP focused less on perfect political thought and more on mobilizing community members and resources for generative social change (Adler). One slogan pictured reads, “Women With AIDS, Dead But Not Disabled,” highlighting the gravity of the situation. In 1993, the CDC finally updated its definition of HIV to include symptoms associated with people assigned female at birth, just a month after Haslip passed away (Adler). The work of women, particularly those of color, within the AIDS movement demonstrated an important push towards a more intersectional fight for health equity and highlighted the resilience of everyone working to uplift the queer community.

Katrina Haslip; NIH Demonstration, Washington, DC. 1990, Nothing Without Us.

03

“Lesbians, HIV, and AIDS: Lesbians and Safer Sex… Are You Serious?”

Though the AIDS crisis (1980s–1990s) is largely associated with gay men, lesbians also bore the burden of the virus (Hollibaugh 223). Creating health education materials written by and for lesbians, these leaders served an essential function in the wellness of their community. One example is the informational pamphlet “Lesbians,

HIV, and AIDS: Lesbians and Safer Sex… Are You Serious?” The pamphlet was created between 1990 and 1995 by the Sheffield AIDS Education Project, a community organization located in Sheffield, UK. Dominant narratives emphasized that women were immune to HIV, excluding them from public health efforts (Hollibaugh 224). From within the community, the idea that “real lesbians don’t get AIDS” prevented the uptake of effective risk-management behaviors (Hollibaugh 219). This pamphlet represents a departure both from prevailing government narratives and harmful community discourse, implementing an expansive concept of lesbian identity for inclusive outreach. Lesbian AIDS organizing was intentionally inclusive of many manifestations of identity, including sex workers, intravenous drug users, and those who still had sexual contact with men (Hollibaugh 223). The pamphlet authors write: “It is important to remember though that if you are sharing needles and syringes or having unprotected sexual intercourse with men for any reason, you could be at risk for HIV” (Sheffield AIDS Education Project 2). This passage demonstrates a postmodern distancing from identity politics, working to include many lived experiences of lesbianism. Postmodern theories move beyond the limitations of traditional identity politics, which “require a unified [...] lesbian identity" (Jagose 62). This expands the reach of this project, touching the lives of many lesbians and others at risk for HIV. The production of community health resources, especially those that employ inclusive concepts of identity, highlights the resilience of the queer community in the face of institutional neglect.

Sheffield AIDS Education Project. Lesbians, HIV, and AIDS: Lesbians and Safer Sex… Are You Serious?. Sheffield AIDS Education Project, [c. 1990]. Wellcome Collection, accessed 8 September 2025.

04

Sylvia Rivera was an activist, advocating primarily for transgender rights as a trans woman herself. Up until her unfortunate passing in February of 2002, she protested and fought for the rights of every person in the queer community, even founding a shelter with Marsha P. Johnson, her

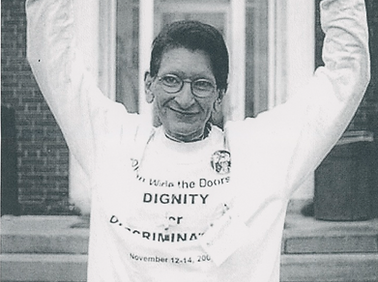

“A Photograph of Sylvia Rivera Celebrating Her Release from Jail” by David C. Distelhorst (2000)

close friend, called Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) (Dunlap). During her life of standing up for others, she participated in a protest put together by the Christian-LGBTQ group, Soulforce. The protest took place at the National Shrine in Washington D.C. in November of 2000 and was done in order to fight back against the Catholic Church’s anti-LGBTQ policies and sentiments (“Our History”). Participants were instructed to come prepared with signs for one’s local bishop, to be prepared for long hours of work, and to most importantly, be ready to get arrested (“Alert: Journey to Justice”). Sylvia Rivera wound up being one of the protesters arrested for her part in the civil disobedience being displayed by Soulforce. This display emphasizes the idea that queerness orders that it must be realized and accepted (Foucault qtd. in Jagose 82); Sylvia Rivera and Soulforce chose to take this idea and implement it immediately through their march on Washington. Queer groups and individuals like Soulforce or Sylvia Rivera who take drastic measures or organize large events like this in order to incite change are the blueprint for how resilience takes place within queer communities.